A Two-Step, Two-Pronged Approach to Binary Classification of Melanoma

CS 230: Deep Learning

Stanford Computer Science, September-December 2021

Abstract

Screening for skin cancer involves either an external examination by a physician or a biopsy of the lesion. These methods are either subjective or invasive, therefore there is a need for an effective screening technique that does not involve subjective examination or invasive techniques. Many people have turned to deep learning as a solution to this problem. Many existing methods include training CNN ensemble models, image segmentation, adding metadata, and using transfer learning in order to improve classification accuracy [3]. In this paper, we use the SIIC-ISIC 2020 Challenge dataset and take a two-step, two-pronged approach to binary classification of images of skin lesions as either melanoma or no melanoma [4]. The first step involves using a U-Net trained on the HAM10000 dataset to produce masks of the images of the ISIC2020 dataset prior to CNN input [5-7]. The mask and image are then concatenated and inputted into a CNN architecture. Based on literature exploration, we implement a VGG model, a Siamese model adopted from Messina et al, and an EfficientNet model that was used in the winning solution to achieve an AUC of 0.9442 [12, 15]. Additionally, we concatenate one-hot-encoded metadata and the output of the CNN model and put it into a final two-layer Dense network. Our best CNN architecture is the Siamese model, and combined with the rest of the pipeline, achieved a test AUC score of 0.831. The results show the potential for a combination of methods and pipelines to be used in binary image classification for skin lesions. Further work is needed to truly explore how a two-step, two-pronged approach can be best engineered.

Introduction

The usual method of screening skin disorders is either via external examination by a physician or a biopsy, in which a scraping or snipped part of the skin is used to determine the proper class of skin lesion. These methods are quite subjective and thus not very effective. There is a need for an effective screening technique that does not involve subjective examination or invasive techniques. For example, squamous cell carcinoma is often misdiagnosed as basal cell carcinoma which is less dangerous, ultimately delaying time to proper treatment [1]. Melanoma is another type of skin cancer that is often misdiagnosed; physician diagnosis is only accurate roughly 65-80% of the time [2]. The current screening technique, involving physicians and other providers examining the skin of patients, is very subjective and can depend heavily on experience.

Therefore many people have turned to deep learning as a solution to this problem. Using computer vision, there is potential to improve screening of skin lesions so that patients do not have to go through an invasive procedure and more dangerous types of cancers are caught earlier. By predicting the level of danger of a skin lesion that is presented via an image, we can both eliminate patient discomfort and decrease subjectivity during screening. In the real world, patients could take pictures of their skin lesion and use an app to determine the severity of the lesion, thereby enabling them to take further action if indicated as dangerous.

Classification of skin lesions using deep learning is an application that has been widely explored. Many methods include training ensemble models, segmentation, including metadata, and transfer learning in order to improve classification accuracy [3]. In this paper, a U-net is first used to segment and mask skin lesions. Binary classification of lesions (benign vs. malignant) is the next step. Various CNN architectures are tested combined with a fully connected network that takes as input metadata of the image including patient sex, age, and location of the lesion. These approaches are all based in literature and are implemented using the SIIM-ISIC (International Skin Imaging Collaboration) Melanoma Classification Challenge competition dataset from 2020 [4].

Related Work

There is a lot of previous work related to this application. A systematic review paper that analyzed 13 different skin cancer classification techniques using CNNs found that fit into two broad approaches: CNN as a feature extractor, and transfer learning with ensemble models [3].

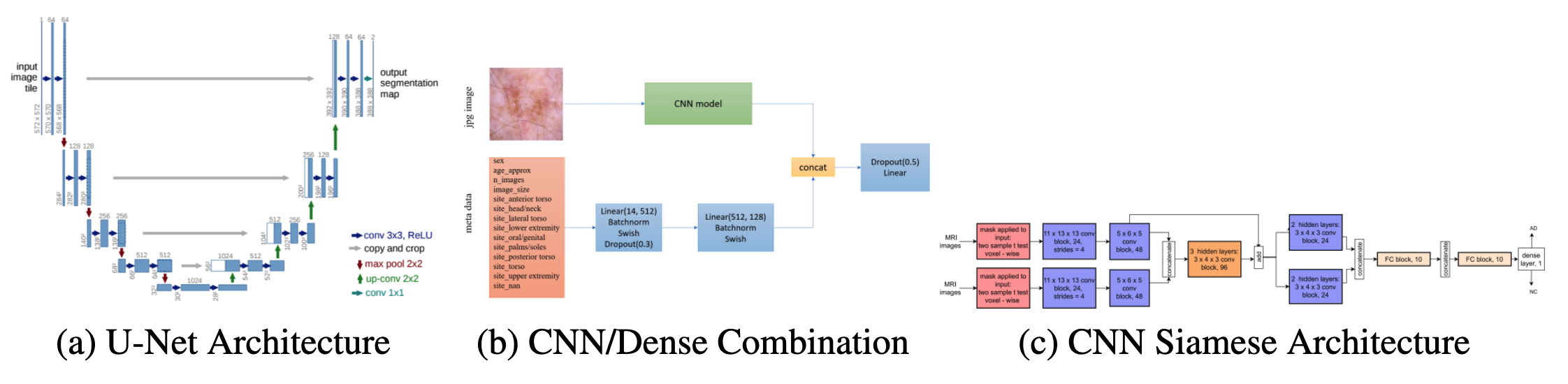

Feature Extractor Using CNNs as a feature extracting tools has been used in relation to skin cancer classification. For example, the HAM10000 dataset (ISIC 2018 dataset) included masks for each skin lesion that identified the location of the lesion within the image [5]. One team integrated a U-net directly into their classification architecture and achieved 93.1% accuracy, a sensitivity of 94.9%, and a specificity of 92.8% for classifying melanoma versus non-melanoma [6]. A U-net is a CNN architecture that was built for biomedical image segmentation [7]. The architecture of a U-net can be seen in figure 1 (left). In this paper, we build off of some of these techniques and implement a U-net trained on the HAM10000 dataset before using it to segment the skin lesion images from the SIIM-ISIC 2020 competition dataset prior to classification.

Transfer Learning and Ensembles Some high-performing models for skin lesion classification are built from scratch based roughly on previous CNN architectures. Many commonly used existing pre-trained CNN architectures in biomedical image classification applications include MobileNet, ResNet, EfficientNet, VGG, Inception, Xception, and GoogLeNet [8-12]. For example, Bi et al entered the ISIC 2017 challenge and used a pre-trained ResNet in a two-step approach to image classification; first perform lesion segmentation then lesion classification. They achieved an average binary AUC of 91.3 [11]. Additionally, the winning solution to the SIIM-ISIC 2020 challenge used an ensemble of 18 different EfficientNet models pre-trained on ImageNet, some with metadata as additional input into the network [12]. They combined the CNN ensemble model fit on the images and a two-layer dense network fit on image metadata (such as sex, age, lesion location). The architecture of their metadata models can be seen in figure 1 (center). Their ensemble achieved a test AUC of 0.9442. Since we are using the same dataset, this is the metric that we are trying to beat. In this paper, we use a similar solution and evaluate various CNN models (including pre-trained models) and a two-layer dense architecture trained on metadata to classify skin lesions as benign or malignant (melanoma vs. no melanoma).

Training from Scratch A few papers have demonstrated use of CNN architectures that have been trained from scratch and have been successful in biomedical applications. For example, Nasr-Esfahani et al used a k-means classifier for segmentation and a two-layer CNN model images to classify lesions as melanoma vs. benign [13]. They trained the model on 136 images and achieved a sensitivity of 81%, a specificity of 80%, and an accuracy of 81%. Another example of training from scratch is from Spasov et al who used a Siamese-type CNN architecture for classification of MRI scans regarding Alzheimer’s disease [14]. Messina et al adopted this architecture and simplified it for their purposes [15]. Notably, their input was masked MRI images, similar to the input used in the present study. Thearchitecture Messina et al implemented can be found in figure 1 (right). In this paper, we evaluate the use of the Siamese model in binary image classification.

Figure 1: Model architecture of implemented solutions [7, 14, 15].

Dataset and Features

The present study uses two separate datasets for different purposes. The ISIC 2020 dataset in- cludes images classified as melanoma/non-melanoma and will be used for image classification. The HAM10000 dataset includes images and masks and will be used to train the U-net prior to segmenting ISIC 2020 images.

HAM10000 (ISIC 2018 Challenge) The HAM10000 dataset was the dataset used for the ISIC 2018 competition [5]. It contains over 10,000 images with metadata containing diagnosis and method of diagnosis. The dataset also includes masks for each skin lesion. In the present study, we use the HAM10000 images as X and masks as y to train the U-net for image segmentation. Since the ISIC 2020 dataset does not include masks, the U-net will be trained using this dataset instead. We pre-process the images and masks by resizing to shape (128, 128) and normalizing to ensure input is within the [0, 1] range. Masks are read in as binary integers (0 = no lesion in pixel, 1 = lesion).

SIIM-ISIC 2020 Challenge THE SIIM-ISIC 2020 Challenge dataset contains over 33,000 images containing skin lesions as well as metadata for each image, including sex of patient, age, and location of skin lesion. The dataset also includes labels for each image (0 = no melanoma, 1 = melanoma). However, the dataset is very imbalanced, with only 584 images labeled as melanoma. Therefore we balanced the dataset by randomly sampling from the benign images with a sub-sample factor equal to the fraction of positive images in the dataset. We resize images to shape (224, 224) and normalize with the same method as the HAM10000 images to ensure input is within the [0, 1] range.

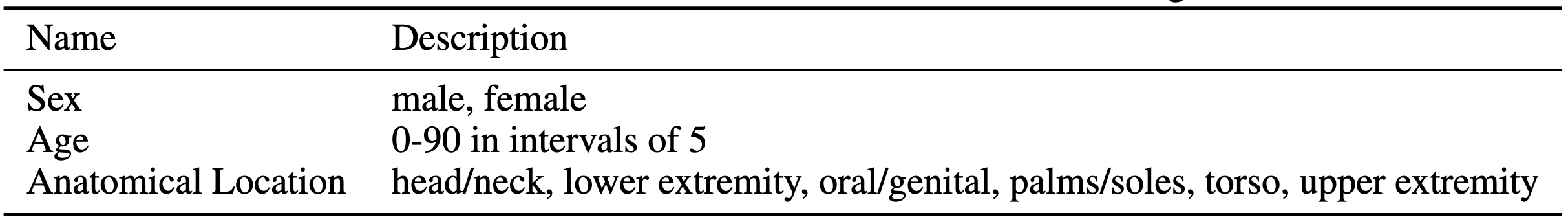

Metadata The metadata included for each image that is of interest is included in table 1 along with each class option. We used one-hot-encoding to process metadata for input into the dense network. We chose to include sex of patient, age (in intervals of 5), as well as anatomical location of skin lesion. Patient metadata is extremely important for diagnosis in practice, therefore is considered in the model architecture for prediction of skin lesion diagnosis.

Table 1: Features Included in Metadata OneHotEncoding

Methods

The entire pipeline consists of a two-pronged, two-step approach taking in the image and metadata as X and binary label as y. The first step is to input the data through the U-Net model to achieve the mask. The original image and mask are then concatenated together and inputted into the classification architecture which is directly based on the combined CNN/Dense architecture from the winning SIIC-ISIC solution that takes metadata as input as well [14]. Multiple CNN architectures were implemented, including a VGG model, Siamese model seen in Messina et al, and a pre-trained EfficientNet similar to that used in the winning solution [15].

Segmentation using U-Net The U-Net was implemented based on the architecture seen in figure 1. The HAM10000 dataset is rather imbalanced, with roughly a 5:1 ratio of benign to malignant. We first believed that this would lead to poor performance when segmenting a balanced benign/malignant dataset due to optimization on an incorrect distribution. We built a U-Net using Keras and trained it on a balanced sample of the HAM10000 images and masks (roughly 3500 examples) with a train/validation split of 0.1. We trained for 20 epochs using a batch size of 64, the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 1e-4, and binary cross entropy as the loss function. We achieved 71.4% validation accuracy.

Based on this performance, we re-evaluated the data used and instead decided to include all data to achieve more confident performance from the model. Using all data and the same train/validation split, we achieved a validation accuracy of 96.03%.

Using this trained U-Net, we obtained predicted masks for the images included in the SIIC-ISIC dataset. We resized images from (224, 224) to (128, 128), inputted into the U-Net, and then resized the predicted masks to (224, 224). We then concatenated the original images of shape (m, 224, 224, 3) and the predicted masks of shape (m, 224, 224, 1) to obtain our X values, masked images with shape (m, 224, 224, 4) with an additional channel that can be interpreted as an alpha channel.

CNN Model Architectures

Each individual CNN model was implemented using Keras. All CNN models used a train/validation/test split of 0.8/0.1/0.1, Adam optimization with a learning rate of 1e-5, binary cross entropy as the loss function, a batch size of 64, and were trained for 150 epochs. CNN output and metadata Dense output is concatenated together and put through a two-layer Dense network (64 units and 1 unit, respectively) with sigmoid activation in the final layer. This was determined throughout the training process, where the number of layers and number of units were hyperparame- ters. Among the architectures tried, this combination was found to achieve the best performance. To prevent overfitting, we used Dropout, L2 regularization and He initialization for the Dense layers before CNN/Dense concatenation as well as after.

VGG The VGG model was manually coded using Keras and is identical to VGG16 with a few changes. We coded a VGG block function, which performed convolution and max-pooling a given number of times depending on input to the function. We implemented a 4096-unit Dense layer at the end of the VGG architecture with He initialization and L2 regularization prior to connecting with metadata Dense layers.

Siamese The Siamese CNN architecture is an extension of Messina et al with a few alterations [15]. For one, we replaced the convolution blocks with VGG blocks. We also changed the kernel size and number of filters for each convolution. We implemented a 256-unit Dense layer at the end of the Siamese architecture with He initialization and L2 regularization prior to connecting with metadata Dense layers.

Transfer Learning To implement transfer learning, we used EfficientNetB0 pre-trained on ImageNet. Pre-trained models that are integrated in Keras take 3-channel images as input, therefore my (m,224, 224, 4) input could not be used. Instead, we multiplied the original image by the mask to get a masked image with 3 channels, therefore changing shape back to (m, 224, 224, 3).

Results

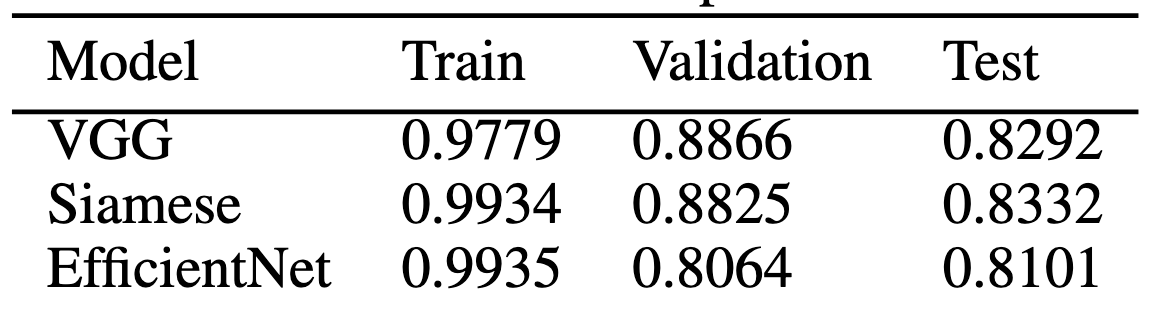

Table 2: AUC Scores of 3 Implemented Models

Segmentation using U-Net Using the HAM10000 dataset, we evaluated the training of the U-Net model. We achieved a maximum validation accuracy of 96.03%. Plots of loss and accuracy as well as sample masked images can be seen in supplementary figure 1. A validation accuracy of 96.03% suggests that the trained U-Net model would perform well with previously unseen data, such as images from the SIIC-ISIC 2020 Challenge dataset. Based on this, we concluded that the U-Net would be a useful tool in adding additional input to the CNN architecture.

ClassificationPlotted results of the VGG model, Siamese model, and transfer learning model using EfficientNet can be found in supplementary figure 2 and final AUC values for train/validation/test sets can be found in table 2. Based on these results, we can conclude that the VGG, Siamese, and EfficientNet models all performed comparably, with the Siamese model being the highest performing on the test set with a test AUC of 0.8332. This performance of the Siamese model is surprising. Both VGG and EfficientNets have been used in this application far more often compared to a Siamese approach and therefore were expected to perform much better, especially because EfficientNet is pre-trained. The Siamese model was also manually designed, straying from the original architecture in figure 1 (right). Despite these reasons as to why we believed the Siamese model would not perform as well, it was very comparable to the VGG and EfficientNet performance, and in fact outperformed on the test set. This suggests that dual pipeline approaches may be useful for skin lesion classification. These AUC values also suggest that my models were overfitting, indicated by the high training AUC compared to validation and test AUC values.

Conclusion

Compared to previous results, we obtained AUC results that are within range of other high-performing solutions to problems similar to this. Many of the previous methods used either a two-step approach (segmentation + classification) or a two-pronged approach (images + metadata). In this work, I combined these approaches into a two-step, two-pronged approach that uses image segmentation along with image + metadata classification to achieve the highest performance possible. We expected to place similar to other high-performing methods (AUC score > 0.8) and we can conclude that we achieved this goal, with our best AUC score equal to 0.8332. We however did not beat the current best AUC score of 0.9442 [12].

Next steps of this work include decreasing the amount of overfitting in the models as well as building an ensemble model of multiple CNN architectures similar to above. We could also use techniques such as Image Augmentation to prevent overfitting. We could also combine multiple datasets to decrease overfitting. This work has shown the potential for a combination of methods and pipelines to be used in binary image classification for skin lesions. Further work is needed to truly explore how a two-step two-pronged approach can be best engineered.

Contributions

All work was completed by Tom McIlwain, M.S. Candidate in Stanford University’s Department of Bioengineering.