Designing a High-Dimensional Environment for Evaluating Decoder Adaptation Algorithm Performance in Neural Interfaces

Undergraduate Capstone Project - University of Washington, 2019-2020

Abstract

Brain-machine interfaces (BMIs) are being heavily researched at the moment for their incredibly ambitious applications such as controlling a robotic arm [1]. The effectiveness of a BMI can be heavily influenced by the method of decoding, the way in which neural activity is processed and mapped to a response on a computer. A poor decoder will lead to poor performance using the neural interface. To combat this, recently there have been a lot of studies surrounding the use of machine-learning to improve the decoders over time [2, 3, 4]. Closed-loop decoder adaptation (CLDA) is used to adapt the decoder in a closedloop neural interface setting in which the user is sending a signal and receiving feedback, and CLDA algorithms have been heavily researched in low-dimensionality settings. However, many BMI applications involve the user controlling multiple dimensions, thus these algorithms need to be tested when the user is performing a more complex task. This study outlines building an environment in which to test three CLDA algorithms (Batch algorithm, SmoothBatch algorithm, and Adaptive Kalman filter) in higher dimensions. The higher dimensional task is an expansion of a normal center-out task. A traditional center-out task involves the user controlling a cursor in two dimensions moving to and from a target on the screen. This has been expanded to include two cursors to double the amount of dimensions that the user is controlling. The cognitive difficulty of paying attention to two cursors is quantified using a two-cursor, one-dimension task in which two cursors both move in one dimension. Instead of a BMI, the study uses a kinematic interface, where a motion-capture Cyberglove records hand movements which are used to represent neural activity to control the cursor. The result of this study is an environment that is capable of testing decoder adaptation algorithms using a kinematic interface.

Video: User wearing Cyberglove attempting to control two cursors early in a session.

Introduction

Brain-machine interfaces (BMIs) connect the neural activity of the brain to a computer or other electronic machines. The user of the

BMI can modulate their neural activity to induce a response by a machine. BMIs can tap into the brain’s innate plasticity to

train the brain to form new connections. There are many applications of BMIs, but some of the most prominent is the use of BMIs

in individuals after a spinal cord injury or limb amputation. Collinger and colleagues published a study which had a subject with

tetraplegia use a BMI to control a neuroprosthetic [1]. The prosthetic arm was highly complex and moved in seven dimensions. The

study found that the user was able to effectively control the limb, reaching targets consistently after some training and was able

to handle objects intuitively, indicating a change in the neural activity allowing the user to learn the task. However, it took 13

weeks of training for the user to achieve reliable control of the robotic arm due to the high dimensionality of the task. One

factor that can explain this requirement of a long duration of training to achieve adequate control of a neural interface is the

initial decoder used to predict the best estimate of the motor intent based on the neural data of the person.

The decoder’s purpose

is to map neural activity inputs into a response by a computer. The accuracy of the decoder, i.e. how correct the mapping is between

neural activity and response, is incredibly important and a poor decoder can have detrimental effects on the entire system.

Therefore, it is important that a neural interface has an accurate decoder to allow for optimal performance when the subject is

performing a task. However, it is difficult to build an accurate mapping based on limited initial data.

As a result, machine

learning techniques have recently been used to improve the decoder as the subject performs the task, allowing for high accuracy

over time despite a poor initial decoder [2, 3, 4]. It is important to note that when using machine-learning in this context, the

interface is both improving the human’s connections by taking advantage of neural plasticity as well as the decoder parameters used

to match the neural signal of a human to the response of the computer. In other words, the human and the decoder are ‘coadapting’ to

one another. To explore this machine-learning approach in closed-loop neural interface settings, in which the user is sending a

signal and receiving feedback, studies have been done surrounding the use of closed-loop decoder adaptation (CLDA) algorithms [4].

There is a lot of research in this field at the moment aiming to find the best algorithm based on the rate of learning as well as

final performance in order to improve the mapping between the user and the computer response, thus creating a more accurate BMI.

Pierella et al. published a study which used a body-machine interface (BoMI) to test the effectiveness of different adjustments

made to decoder adaptation algorithms [2]. The researchers implemented a principle component analysis method into the decoder to

detect specific patterns the subject would use to control as well as the degrees-of-freedom that the user had trouble controlling.

The results of the study showed that the decoder using principle component analysis had a marked improvement over the original

method in the performance of the subjects controlling the cursor. Another study by Danziger and colleagues compared the performance

of subjects using a kinematic interface when implementing two machine learning algorithms, LMS gradient vs. Moore- Penrose pseudoinverse

transformation [3]. These studies, among many others, have shown empirically that using machine learning to improve the decoder

has the potential to drastically improve the accuracy of the BMI.

However, many of these studies involve a user performing a

simple two-dimensional center-out task to test the efficacy of the CLDA algorithm. This is a limitation of the current research

as many relevant BMI applications require humans performing tasks which are much more complex involving multiple degrees of

control, as seen in the study where the subject controlled a 7-dimensional prosthetic, which took many weeks to learn [1]. One

of the most researched is the use of BMIs to control a neuroprosthetic, and many neuroprosthetics currently used in BMI research

are a robotic arm with 5 or more degrees of freedom. These robotic arms have many dimensions and are thus much more difficult to

learn to control compared to controlling a cursor moving in two-dimensions in a simple center-out task. Wodlinger et al. authored

a study published in the Journal of Neural Engineering which evaluated the performance of a human subject using a BMI to control a

10-dimensional robotic arm [5]. The authors found that the human subject was able to adequately control the arm, but the performance

varied greatly depending on the calibration of the decoder. This problem could be solved using a CLDA algorithm to improve the

decoder. By iteratively improving the decoder parameters, the initial decoder parameters defined by the calibration method have

much less impact on the final performance of the subject, thus the performance is hypothesized to vary much less depending on the

initial decoder and increased dramatically over time. However, there is a significant lack of studies exploring and evaluating the

efficacy of CLDA algorithms in high-dimensional tasks.

This study aims to build a higher-dimensional environment to provide a space

to evaluate the use of CLDA algorithms in humans performing both a simple task as well as a more complex task with more cognitive

burden in order to assess the efficacy of CLDA algorithms in a broader array of BMI applications. There are many design specifications

that must be considered when developing CLDA algorithms for use in higher-dimensional BMI tasks. Dangi and colleagues explored the

design elements that are most important when designing a closed-loop decoder adaptation (CLDA) algorithm for use in BMIs [4]. The

authors found four key design elements when designing a CLDA algorithm: adaptation timescale, selective parameter adaptation, smooth

decoder updates, and intuitive CLDA parameters.

To build this environment, we needed a method to represent a brain-machine interface.

To achieve this accurate representation of a BMI, we developed a kinematic interface using a Cyberglove, a motion-tracking data glove. A user wears the Cyberglove and generates hand movement data, using their hand to control a circular cursor moving to and from a target. When using a BMI, both the human and the computer simultaneously learn and adapt to one another. The kinematic interface utilizes this “user in the loop” system as it involves both a human learning as well as improving the decoder. Therefore, the algorithm’s performance is hypothesized to be directly applicable to the use of mapping algorithms in BMIs.

This project aims to build an environment in which we can evaluate three commonly used CLDA algorithms in a highdimensional task using a kinematic interface as a model of a BMI based off of these key design elements. The algorithms used in this study are the Batch algorithm, the SmoothBatch algorithm, and the Adaptive Kalman filter, evaluated in a simple two-dimensional one-cursor center-out task previously [4, 6]. The design elements mentioned above are distinct among these three algorithms, thus testing these algorithms is appropriate when evaluating the use of various CLDA algorithms in a higher dimensional task.

The experimental process begins with an experiment involving a two-dimensional center-out task where the subject controls one cursor, then is scaled up to include two cursors. The subjects initially control one cursor in two dimensions, then two cursors moving in one dimension in order to assess the cognitive burden of moving multiple cursors. Then the task is altered so that the cursors both move in two dimensions in a center-out task in order to test the efficacy of the algorithm in higher dimensional tasks. With two cursors both moving in two dimensions, this raises the dimensions of the task from a 2-dimensional task to 4-dimensional. This study delivers a high-dimensional environment in which adaptation algorithms can be assessed for both a low-complexity and a highcomplexity task and is able to determine how useful CLDA algorithms are in the application of higher-dimensional human-controlled BMIs.

Development of Design Specifications

Kinematic Interface Design

The first design criterion that must be determined for this study is the type of decoder that will be used to map the hand movement data to cursor kinematics. There are many types of decoders that have been previously used in neural interfaces, such as recurrent neural networks, Bayesian linear regression, and point process filters [7, 8, 9]. The Kalman filter has been previously used when evaluating CLDA algorithms and is often the general approach in many neural interface studies, thus this study will continue with this standard [4, 6, 10]. The Kalman filter is one of the most commonly used decoder because it is an excellent predictor of future states of objects. The Kalman filter is a state-based model, which uses two models to predict the state of the cursor: a state-transition model and an observation model. This decoder uses the previous estimate and takes in a measurement from a related signal to predict another estimate. The state-transition model predicts the cursor kinematics based only on the previous state of the cursor, while the observation model updates this prediction using the glove state. In other words, the Kalman filter uses the previous state of the cursor as well as the glove signals to predict the next state of the cursor kinematics, allowing for improved performance of the decoder because the prediction is now based on multiple measurements compared to other decoders that do not model state kinematics of the cursor.

The type of control scheme used in the kinematic interface must also be considered. The data generated from the hand movements of the user could either determine the velocity or position of the cursor. In a study by Marathe and Taylor, different decoding methods were compared using the performance of subjects using BMIs [11]. The authors found that decoding position, velocity, or reach goal has a significant impact on user performance. When using direct decoding, i.e. position of the hand controlling position of the cursor or similarly velocity-to-velocity, the users found that it was impossible to overcome decoding errors of position. When the cursor velocity was controlled by position of the hand (position-to-velocity), the system was easy to learn for the users and resulted in better performance. Based on this study, position-to-velocity will be used in this study.

Algorithm Adaptation Design

Apart from the design of the kinematic interface, there are four key design elements of the decoder adaptation algorithms that must be considered when testing the efficacy of these algorithms detailed in the previously mentioned study coauthored by Professor Orsborn: adaptation timescale, selective parameter adaptation, smooth decoder updates, and intuitive CLDA parameters [4]. The algorithms explored in this study, the Batch, SmoothBatch, and Adaptive Kalman filter, all differ in these design elements, thus the result of this study is an environment where one can achieve a broad estimate of the performance of many additional CLDA algorithms with different design elements in high dimensional tasks.

The adaptation timescale describes how often the adaptation algorithm updates the decoder. The study that identifies these four design elements outlined two different adaptation timescales: real-time and batch-based [4]. Batchbased CLDA algorithms update the decoder parameters after a defined period of time within a session, usually every 1.5 to 2 minutes. Real-time algorithms update the mapping every iteration, corresponding to an update every ~31 milliseconds (32 Hz) in the current study based on the maximum sampling frequency of the Cyberglove. The authors found that empirically, batch-based algorithms outperform real-time algorithms. However, a study done by Shanechi, Orsborn, and Carmena found that spike-event-based adaptation (real-time) allowed for quicker convergence to final performance level compared to batch-based algorithms [12]. The Batch algorithm and SmoothBatch algorithm are both batch-based while the Adaptive Kalman filter updates the parameters in real-time, therefore this study evaluates both of these approaches in a higher dimensional task.

The second design element, selective parameter adaptation, is relevant when updating the decoder’s parameters. The decoder may have multiple parameters that may be updated, such as a Kalman filter which has 4 different matrices that can be adapted. It is important to consider which of these parameters should be updated over time. The matrices of the Kalman filter that correspond to the cursor kinematics will not be updated, as the basic physics of the cursor should remain the same throughout the study, where the velocity decreases over time to represent inertia of the cursor and friction within the system to provide intuitive physics, easy for the subject to understand. The study outlining these design elements found that updating all the matrices within both the state-transition model and the observation model of the Kalman filter resulted in the cursor becoming stationary, therefore this study will only update the observation model matrices to keep the cursor kinematics static [4]. Smooth decoder updating is the third design specification that must be considered.

Smooth decoder updating is in contrast to a simple decoder updating method in which the decoder is updated based on the current state of the system with no regard to prior decoder states. Smooth decoder updating uses a weighted average with the previous decoder’s parameters to alter the current parameters in order to prevent a significant change in the parameters based solely on the most recent batch or iteration. This is important because data generated within the most recent batch or iteration that would be used to update the mapping may be unreliable due to a poor initial decoder. The Batch algorithm simply uses the previous batch data to update the parameters without taking into account the previous parameters, thus does not utilize this smooth decoder updating. However, both the SmoothBatch and Adaptive Kalman filter algorithms uses weighted averages to smoothly update the decoders. By using these three algorithms in the study, we are able to explore both simple decoder updating and smooth decoder updating in high dimensional tasks.

Finally, the CLDA parameters should be implemented to be intuitive. These intuitive parameters are separate from the Kalman filter matrices and include parameters such as weights of previous decoder mappings when performing a weighted average in the SmoothBatch or Adaptive Kalman filter, the step-size of the stochastic gradient descent within the Adaptive Kalman filter, and more should be designed to be relatively intuitive in order to make the system much easier to understand and manually adapt. To make the system more intuitive, these parameters should be within a set range, ideally [0, 1], for easier exploration of possible optimal parameters and thus simpler tuning.

Because each of these three algorithms differ in some critical design criteria, exploring CLDA algorithm use in complex tasks using these algorithms provides a more general estimate of adaptation algorithm performance in BMI applications.

Ethics & Regulations

When performing the studies using the kinematic interface, there are not many intensive regulations that must be followed. Testing the interface during development will be done internally by members within the lab, therefore regulations involving test subjects do not apply. However, when performing studies using subjects outside the lab, approval of the study by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) is required beforehand. Unfortunately, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the IRB was not able to approve this study, therefore this study does not include any experiments involving human subjects. If the algorithm is eventually tested within brain-machine interface applications on animals such as the rhesus macaque (beyond the scope of this study), there are strict guidelines that must be followed. The studies must be approved by the University of Washington Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), a group that evaluates the ethics of the proposed animal studies.

There are many considerations of this project in regards to the impact on the outside world, however there are not many concerns regarding this study’s impact on the environment, as this study is using no external resources besides electricity to power the computers. The economic constraints are also of little concern, as all materials have already been purchased and no subject receives compensation for their participation. If any new resources are needed, they are covered under the grants of the Orsborn Lab. As there is no risk to any subject when using the non-invasive kinematic interface, there are not many safety concerns for the study compared to a study involving a BMI which is much more invasive. Some of the safety concerns include the user developing a rash, injuring their hand through repeated movements, or the spread of disease if not disinfected. The global and cultural impacts of this study are also limited as the scope of this project is relatively narrow. There is a very small population that this project, if continued to the clinical environment, would impact. Presently, this study’s results are only impactful on people using BMIs.

When working with interfaces that involve humans controlling something, there should always be questions regarding the ethics of how the control mechanism works. In kinematic and brain-machine interfaces, the human has control of the computer’s response. But when using the adaptation algorithm, the decoder’s parameters are always changing, so the level of control by the human may shift. Therefore, the question of how much control the subject actually has should be raised. The impact of loss of control varies dramatically depending on the device being controlled. For example, a loss of control has minimal consequences in brain-machine interfaces when doing a center-out task, and less so in kinematic interfaces, because the consequences of the human losing control is a failure to move a cursor in a controlled manner. However, in the far future when brain-machine interfaces move on to broader applications, such as controlling your phone or even your car, then that question is far more important to consider. There will be significant consequences if the human loses control. Another ethical consideration is the privacy of data. Brain-machine interfaces record neural data, and once translated to a response on the computer, future applications such as the previous answers could render a risk of a data breach. There will be no personal data taken from subjects, so a data breach in the scope of this experiment is not a huge concern as there are no serious consequences.

Materials and Methods

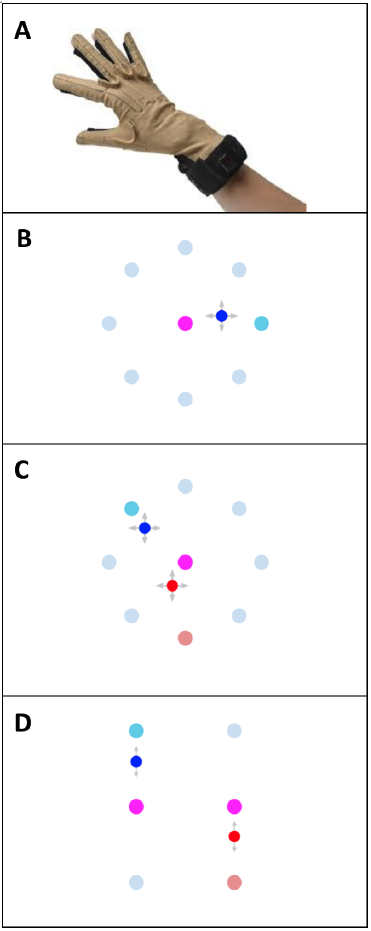

Figure 1: Set up of the center-out tasks. A. Cyberglove. B. One cursor, two-dimensional task (1C-2D). C. Two cursors, two-dimensional task (2C-2D). D. Two cursors, one-dimensional task (2C-1D).

This project uses a CyberGlove II motion capture data glove to measure hand movements from the subjects. These hand movements will control cursor(s) on a computer screen. The CyberGlove has 22 sensors on it. Kinematic interfaces, and specifically CyberGlove motion capture gloves, have already been used when evaluating machine learning in human-machine interfaces [3].

The center-out task is designed based on previous studies by Professor Orsborn, using one cursor in two dimensions [4, 6]. There are three individual designs of a center-out task used: a one-cursor two-dimensional task (1C-2D), a two-cursor one-dimensional task (2C-1D), and a two-cursor two-dimensional task (2C-2D). The 1C-2D experiment begins with one cursor in the center of the screen. 1 of 8 targets surrounding the cursor in a circle is shown at random and the user must move the cursor into the target within a maximum trial duration of 5 seconds and hold the cursor within the target for a hold-time of 400 ms. If the user fails to move the cursor to the target in time, the trial is failed and the next trial uses the same target. If the user is successful, a new target is generated at random. After a successful or failed trial, the user must move the cursor back to the center and hold it there for 400 ms in order to begin a new trial and reveal the next target. This task is exactly the same in the 2C-2D design, but there will be two targets on screen with corresponding colors to the two cursors (blue and green).

In order to compensate for the increased difficulty of controlling two cursors, we will estimate the cognitive burden, i.e. how difficult it is to control two cursors compared to one. To evaluate the cognitive burden of moving two cursors, the center-out task is altered so that two cursors are both moving in one dimension (2C-1D), keeping the total number of dimensions (2) equivalent between the 1C-2D and 2C-1D tasks. Thus, the difference in performance between the two tasks is due to the extra cognitive burden the user faces because they must pay attention to two cursors rather than one. The two cursors start in separate locations, at the horizontal center of the screen and offset either in the left or right direction from the vertical center. The cursors are only able to move vertically towards a target above or below the center of the starting point of each cursor. Refer to figure 1 for a visualization of each of the three setups.

A Kalman filter is used as the decoder to translate the glove data to cursor kinematics. The initial matrices are calibrated using data when the user is passively watching the cursor move in a straight line to and from a target while moving their hand for 5 minutes (150 trials, each 1 second long plus 1 second where the cursor moves back to the center). The user is not in control of the cursor during calibration. Both the initially generated calibration data and randomly shuffled calibration data can be used to fit the matrices in order to vary the effectiveness of the initial decoder. Refer to Wu et al. for the specific Kalman filter equations used during each iteration [13]. The Kalman filter uses the data generated using the subject’s hand to predict the velocity of the cursor. The state of the glove is a 22x1 vector with values ranging from 0 to 255, and is used to predict the cursor velocity, a 3x1 vector shown below. The constant term 1 is used to account for any non-zero means within the glove state.

𝑥" = [ 𝑣'()*+(,"-.,", 𝑣01)"*2-.,", 1]

Subjects will perform as many trials as possible in three 30-minute sessions. The center-out task is varied across the sessions, moving from the 1C-2D task to the 2C-1D task and finally the 2C-2D task. Each subject will be using one of the three CLDA algorithms tested throughout each session. The subject will either be using passive calibration data or shuffled calibration data.

The decoder is adapted based on the estimation of user intention when controlling the cursor. The specific intention estimation method used is called CursorGoal, and has been used in previous papers exploring CLDA algorithms [9]. The user is assumed to be always trying to move the cursor to the target, so the decoder will be updated based on the difference between the cursor velocity orientation and the direction from the cursor to the target. Ideally the cursor velocity direction would be identical to the direction needed to reach the target. The speed of the cursor remains the same between the predicted velocity using the Kalman filter and the intended velocity.

Evaluation of the performance per trial will be endpoint error when the trial expires as well as time to reach target and is based on many metrics such as success rate of the user, final level of performance achieved, percent of trials correct, and time to converge to final performance.